Music and the Brain

Some friends and I attended a symposium in August connected with the 40th anniversary of the Santa Fe Chamber Music Series, called “Music and the Brain.” It was a meeting of science and art, a look at cutting edge neurological research related to music, and a pragmatic look at how music is used in the fields of health and education. Some of the brain research seemed rudimentary on the surface, “proving what we already know,” but as we learned, overall it represented an enormous advance on the experiments with “clicks and beeps and chinchila brains” of 30-40 years ago. The effort to quantify and scientifically describe the activity of the brain “on music” is often driven by the desire to reinstate music in education and encourage insurance coverage of the use of music with medical patients. At this gathering, the sense of collective good will of the presenters was palpable, and one of the best things about the whole affair. Many of them were also accomplished musicians.

Our small group was somewhat familiar with Oliver Sack’s recent book on music and the brain “Musicophilia,” and some of us saw his PBS TV show “Musical Minds,” but we found most of the material in Santa Fe new and often startling.

Without trying to summarize the presentations or do justice to the presenters (http://musicandthebrainsantafe.com/), here are some individual moments and ideas from the weekend that really got us going. (see two of our group at lunch, with Picasso thinking)

The brain activity involved when we move in response to a rhythm is highly complicated, even at the level of tapping our foot to a metronome. Remarkably, monkeys and other primates cannot be taught this behavior. They can be trained to respond each time to a repeating beat right after it occurs, but they cannot move in anticipation of the beat no matter how long the training is attempted. How can this be? Our closest evolutionary relatives, they use tools, have emotions, play jokes, are highly social. But we are not alone: remarkably, parrots and cockatoos are our partners in moving and grooving. Here is a youtube of Snowball, a cockatoo examined extensively in the lab, who was not trained to dance, is not physically mimicking anyone, can respond to previously unheard music and has developed a vocabulary of his own dance moves and invents new ones. Is this ability something to do with a facility for spoken language?

Then there was the much documented affect of music on the gait and movements of some Parkinson’s patients. In some people, the fundamental “hard-wired” rhythm of walking no longer functions properly. Without it, their movements are halting, disorganized and physically limited. But to the sound of music, chosen to match their individual gait, they may walk normally, their arms and legs physically free. We were told that the brain can relearn the biological rhythms that have been lost, by listening and moving to music. Look at the first few minutes of this video clip after putting the whole address in your browser:

We were told about the man with Parkinson’s who could function independently in the world by wearing a walkman. This enabled him while listening to music to take public transportation, walk and do errands, go out from and return home. One day he experienced the failure of his walkman batteries. Nearing panic, he realized that he could sing or imagine music by himself in his head. Doing this allowed him to continue to get back home safely.

Experiments have been designed to explore the possible connection between sharing music and learning empathy. In one there were 2 groups of very young toddlers. One group had kids bouncing to music while facing an adult bouncing in sync with them; the other group bounced while facing an adult who was out of sync with them. The first toddlers were more apt to help a researcher later on who dropped a pencil out of reach. In another trial, older children who played games together that involved musical accompaniment were more likely to cooperate afterwards than children who played the same games without music.

A music therapist showed a dramatic youtube clip showing an Alzheimer’s patient responding to music with a force of personality and level of speech that was unknown in the years before he was given his favorite music to listen to.

Other patients were shown who had suffered strokes and had difficulty finding and speaking certain words (Aphasia). They responded to a program that started out teaching them to use a singing-like form of speech, which allowed them to find and use previously lost words. Some patients ended up speaking with a subtle raising and lowering of tone, a slightly sing-song voice, with remarkable improvement. We watched one girl as an example of this who had lost nearly half her physical brain in an accident, and her speech was remarkably normal.

There were stories of the power of music to help children with autism, like the example offered by Alan Gilbert, the current conductor of the NY Philharmonic, of an autistic teenager who volunteered to conduct (the speed and loudness of performance) a small group of classical musicians visiting his facility. His “break out” physical and emotional involvement with this had his doctors in tears.

Check out this video of the newly invented Virtual Musical Instrument, VMI, for people who are physically limited. It is not just the joy of the users, but also our gift of being able to do something for someone else that is so transparently on display.

Space precludes going at length into the presentations on the meaning of music for cancer and terminally ill patients. Coping with pain and the retrieval of memory and meaning were subjects. The preciousness of silence was also discussed, creating a lingering perspective on everything we had previously heard.

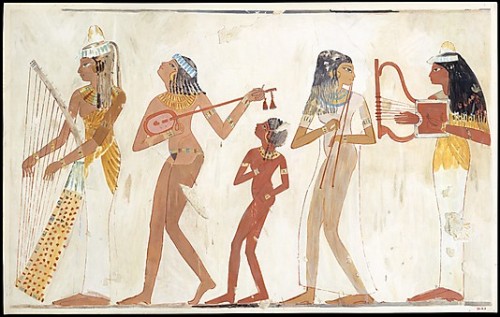

One presenter, Michael Thaut, summing up towards the end of final session, stated that musical structures were basic to the brain, in neurological forms that predated and were more fundamental than those connected with language. He reminded us that the first emergence of modern humans was accompanied by completely developed visual art and flutes that were made to produce perfect octaves, this preceding any complicated technology and probably sophisticated language. In my layman’s mind, I had the thought that with music we are immediately connected with an order beyond and outside ourselves (think mathematics) which is united with our personal emotions and memories.

I was grateful that some music was performed towards the end of the symposium. Welcoming healing and consolation ourselves, we sat listening in the same room where we had attended to highly reasoned arguments and looked hard at statistical graphs and complex brain scans. Was I the only one who felt that I had gone “somewhere else” while listening to the harp and violin and piano, and then “came back” to the speakers’ conclusions?

There is “music,” as in “Music and the Brain,” and there are pieces of music, as in the sound track of our youth, the music of our teens and twenties that is never supplanted. And there is music in real time, performances and listening experiences that are never the same twice. This is what I heard that morning in the music played for us (the following youtube examples of the musical works are not from the symposium):

Small River Flowing (Chinese Folk Song)

A respectful speaker with inclined head relates stories of inescapable fate, wonders, places. Not wanting to disturb the equanimity of the hearer, the tales are told through the charming sound of running water.

Gymnopidies No. 1 Erik Satie

This piano piece reminded me of a college friend who on first hearing this, began crying without knowing why or what for. It can gently dissolve the barrier between daily life and unshed tears.

The Girl with the Flaxen Hair Claude Debussy

Debussy slows forward motion, striving, wanting. We are in an armchair in Proust’s writing room, magic lantern pictures moving on the wall evoking memories and sensations. Not busy making our life, but allowing it to be what it now is.

Chaconne JS Bach

Whatever areas of the brain are normally activated with music, this work must engage almost all others as well. It seems to include the argument of speech, and elicit immense physical as well as moral effort. For every consolation it offers, it also recommends the inescapable path of suffering; and vice versa, all pain is mitigated by the sweetness of music and understanding.

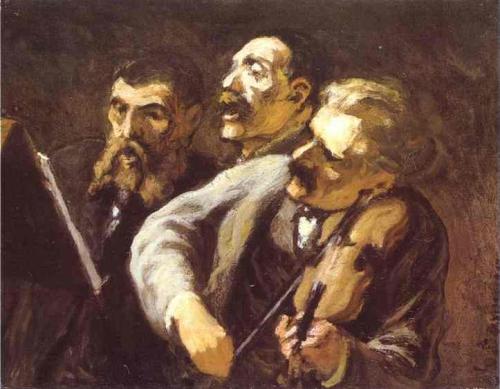

Paintings pictured: “Egyptian Women Musicians,” ca. 1400 BC, tempera on paper; Daumier “Three Amateur Musicians'” 1864, oil on canvas; Rembrandt “King Saul and David,” 1655-60, oil on canvas.

-The skies were beautiful in Santa Fe, and the oldest house in the US which is there, quiet at night.